In Uncertain Times, Nonprofits Must Keep Up With Legal Compliance

04.11.2025 | Linda J. Rosenthal, JD

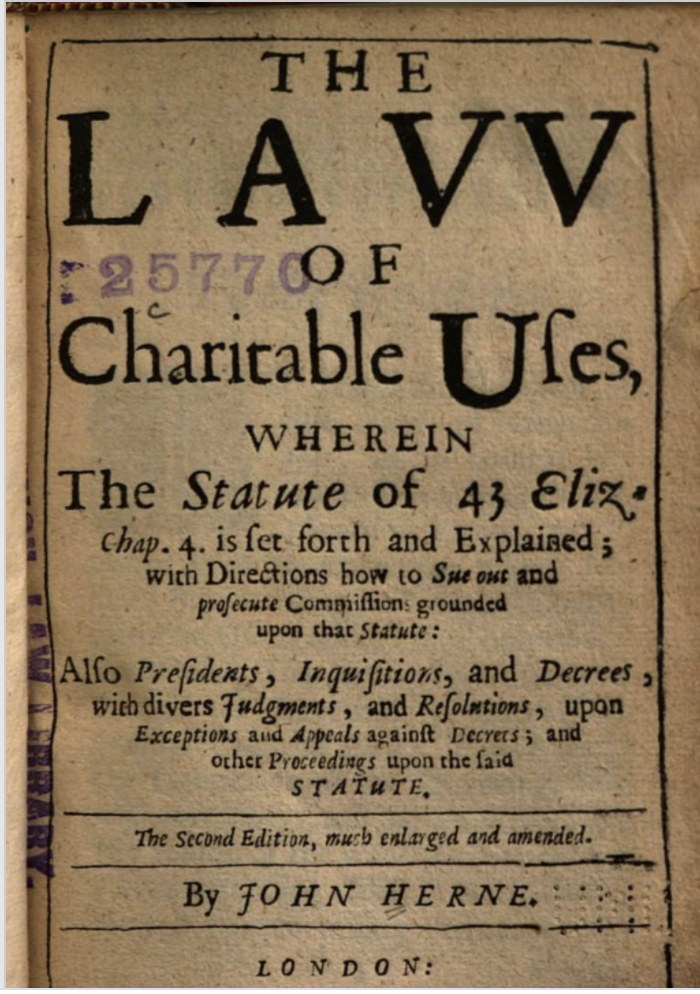

It’s 2021, and we’re still talking about The Statute of Charitable Uses of 1601.

This landmark legislation – the “birth of the modern law of philanthropy” – is not a mere historic relic, dusted off from time to time to remind us that our American legal roots hark back to the common law of Tudor England.

Deeply relevant to this day “… some five centuries later and an ocean away….” it is – or certainly should be – center stage in the United States Supreme Court right now in the case that has the nonprofit sector riveted … and worried.

A ruling in Americans for Prosperity Foundation v. Bonta and Thomas More Law Center v. Bonta [consolidated docket] is expected any day now.

In Donor Disclosure: The Hottest Ticket in Town (May 25, 2021), we set the scene, identifying the parties in this seven-year courtroom drama and pointing a spotlight on the enormous elephant in the room.

Each and every year, two 501(c)(3) organizations file with the Internal Revenue Service the required full Form 990 information return. They submit all attachments including Schedule B. But they refuse to turn over an exact copy of that Schedule B to the California Attorney General’s Registry of Charitable Trust in their annual reporting package to the state. At both levels, the Schedule B, that asks for the names and addresses of the charities’ top donors only, is kept separate and confidential from the rest of the Form 990 that is public information.

When asked why they comply in the first instance with the federal requirement, but aim a fully loaded First Amendment cannon at the state of California, the challenger organizations (petitioners in the Supreme Court, the Ninth Circuit having thrown out their trial court victory) respond with … well, they don’t really have a good answer. See our May 25th post as well as our more recent post, Donor Disclosure: Hottest Ticket (Part 2) (June 2021). There is much more going on in this case than a simple objection to a state’s reporting requirement.

It’s part of a full-blown campaign against 500 years of rock-solid Anglo-American jurisprudence that confirms that (a) modern-day “state attorneys general in the United States” inherited the parens patriae tradition and authority bestowed on the Crown Attorney General in the Statute of Charitable Uses Act of 1601; and (b) they “… still carry primary oversight and enforcement responsibility with respect to the nonprofit sector.” See most particularly, Restatement of the Law, Nonprofit Charitable Organizations (2021) American Law Institute, Chapter 5. “Role of State Governments.”

The challenger-organizations’ legal offensive is little more than [discredited and debunked] “yakety-yak.” Chief among it is the notion that “that state attorneys general have only a minor role in the oversight of charitable organizations in the U.S.”

The stakes in this litigation are high, and there will be consequences well beyond whatever decision the Supreme Court makes. So we’re spending quite a bit of time on the true and (little-known) history of charity regulation in the United States.

In Part 2, we traveled back in time with emeritus law professor James Fishman to late sixteenth century England. In Encouraging Charity in a Time of Crisis: The Poor Laws and the Statute of Charitable Uses of 1601 (2005), SSRN, he masterfully lays out the true and correct historical development.

Here, we’ll bring it up to date, but – first – let’s review a few key takeaways:

Professor Fishman is the author of Nonprofit Organizations: Cases and Materials (5th ed. 2015), a widely used law school textbook. He is also one of twelve distinguished scholars who submitted an invaluable “friend of the court” brief in support of the California Attorney General. See Brief of Amici Curiae Scholars of the Law of Non-profit Organizations in Support of Respondent (March 31, 2021), [“Scholars”].

Of note is the standard “Interest of Amici Curiae.” They identify themselves not only as “professors and scholars of the law of nonprofit organizations” but also “collectively, as officials in all aspects of the administration of nonprofit law (including a list of posts around the nation at the federal and state levels in the administrative and legislative branches). They have also “founded research projects on charities regulation and oversight” and “they assist state Attorney General offices in studying and adopting new approaches to the regulation of charity and charitable solicitation.”

Their rationale for “participating in this litigation” is that “[n]o party in this case represents all three of charity’s key stakeholders: charities, states, and taxpayers who underwrite the charities’ funding.” They want to “aid the Court in understanding how these three interests depend on one another. They also attempt to provide a clearer understanding of state supervision of charities and how that supervision relates to federal tax law.”

It’s important to point out that amici curiae can submit a brief “in support of neither party,” simply to give the court expert perspective. Here, though, they fully support the California Attorney General’s position and issue stark warnings throughout the brief of the significant, long-term damage to the charity sector if the Supreme Court rules in favor of the challenger-organizations. [Scholars, pp. 2-5, 11, 28-30].

Of course, right out of the gate, they confirm the clear and direct link between the Statute of Charitable Uses of 1601 and the development of the American jurisprudence of charity law and regulation up to the present day. [Scholars, pp. 5-6].

In several other excellent amici curiae briefs in this case, there are comprehensive discussions of these and other points, all backed up by well-settled legal authority. See, for example, the brief of the California Association of Nonprofits, [“CalNonprofits”]. Specifically, on the unbroken historical chain from 1601 to the present day, see pp. 2,7.

See also the brief prepared and submitted by the Office of the Attorney General of New York on its own behalf as well for sixteen other jurisdictions: Colorado, Connecticut, Hawai’i, Illinois, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Nevada, New Jersey, New Mexico, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Virginia, and the District of Columbia. [“NY et al.”]. On the continued significance of the Statute of Charitable Uses of 1601, see pp. 2-3.

In the colonial period as well as from the new nation’s first decades, attorneys general have “extensively supervised charitable organizations.” Indeed, the scope has been greatly expanded in the United States “beyond that which existed in England.” This history is particularly well explained in summary form in the brief of the seventeen states. [NY et al, the Statement of the Case].

A few points of note include:

Today, States retain their longstanding authority to supervise charitable organizations typically through the offices of state attorneys general. The nature and extent of that power varies jurisdiction by jurisdiction.

The model of an attorney general with responsibility to protect the interests of the general public (in connection with charitable trusts, assets, and solicitations) is now “firmly rooted” in each and every state, territory and the District of Columbia, according to the National Association of Attorneys General.

Laws that require charities to register and file annual reports “were adopted in aid of the States’ traditional role,” based on the fact that an attorney general “could not carry out his common law duties as supervisor of charitable funds without knowledge of the charities subject to his jurisdiction and the nature and extent of their financial dealings.” [NY et al, pp. 2-3]

“State Attorneys General across the United States still carry primary oversight and enforcement responsibility with respect to the nonprofit sector.” [CalNonprofits, pp. 7-11].

More particularly, “in California as in every other State, the Attorney General is the protector of the public’s trust in the nonprofit sector. The Attorney General has a duty to ensure that assets contributed to charity are used in accordance with the purposes for which they were donated…, and “also is charged with safeguarding the public against fraudulent and deceptive charitable appeals.” [CalNonprofits, pp. 2, 7-11]

In the Restatement of the Law, Nonprofit Charitable Organizations (2021), the “noted professors, judges and lawyers” who authored this authoritative treatise setting out “the legal rules that constitute the common law in [this] particular area,” sum up the centuries-long historical links. “The central role of the state attorney general in the regulation of charities,” they explain, “developed as part of the early English common law. The Crown’s law officers, implementing the Crown’s prerogative as parens patriae, defended subjects that could not defend themselves, including charities….” See official comments to Section 5.01, “Role of the State Attorney General.”

Continuing, they add: “The contemporary role of the state attorney general in the United States in protecting charitable assets and interests, as well as the justifications for that authority, can be traced back to the Crown’s powers over charitable trusts, which were implemented by the Crown’s senior lawyer, the attorney general.”

This point has been expressly accepted by every court that has spoken on the California (or the almost identical New York) rule in question, with the (lone) exception of the trial judge in this litigation now pending in the U.S. Supreme Court. And his legal conclusions as well as findings of fact on the key issue of the powers of the California Attorney General have been decisively rejected.

— Linda J. Rosenthal, J.D., FPLG Information & Research Director